Plots And Points

- Finally, we plot the points by passing x and y arrays to the plt.plot function. So, in this part, we discussed various types of plots we can create in matplotlib. There are more plots which haven’t been covered but the most significant ones are discussed here – Graph Plotting in Python Set 2; Graph Plotting in Python Set 3.

- Plot the ordered pair 6, comma negative 8 into the coordinate plane. So this is a coordinate plane right over here. The horizontal axis here, this is the x-axis.

What is a plot point, and why is it helpful to think in terms of plot points? Read on for a definition and tips for making significant events in your novel or story count:

What is a plot point?

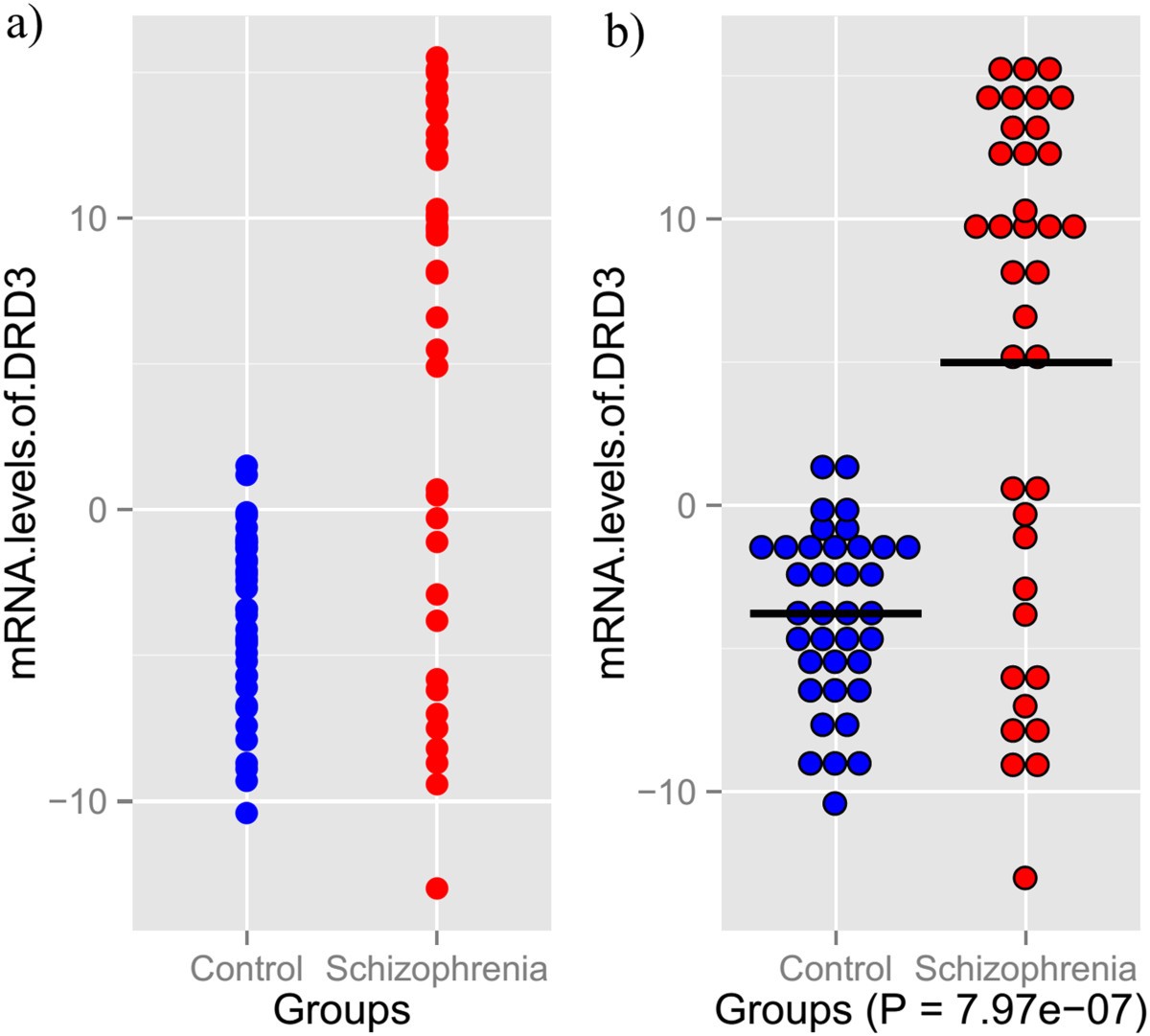

A strip chart is like a box plot with points showing, and no box: In 20: import plotly.express as px df = px. Tips fig = px. Strip ( df, x = 'day', y = 'tip' ) fig.

Many writers attach strict roles and functions to plot points. Some say, for example, a first plot point is a turning point for your character or a point of no return.

The simple Oxford Dictionary definition:

‘A particularly significant part of the plot of a work of fiction, especially a film or television drama.’

Thus plot points don’t necessarily have a specific function. They are simply key events in your story that are important to the whole.

A character hiding a gun in their glove compartment is a plot point. A character eating breakfast is not. Unless, to use a silly example, the first mouthful transports them to an alternate universe.

As the definition makes clear, plot points are a common topic in screenwriting. Here, focusing on plot is particularly important, since in an hour-long episodic format, for example, screenwriters need to make sure something happens to keep viewers tuning in week after week. For these reasons, starting and ending with plot points that are purposeful and create momentum in story arcs is key.

Even though your book might not be released in episodic format like a Dickens novel, plot points are a useful concept. Whether your reader does the equivalent of ‘binge-watching’ and reads your book through the night or paces themselves depends, in part, on how badly they want to find out the next plot point.

So how do you find plot events that hook readers on your story and characters?

1. Draw intriguing plot points from your central idea

You can spin all kinds of great plot points out of a strong central story idea [complete the first step of Now Novel’s dashboard to find or tweak your own].

Take, for example, Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s classic novel, Love in the Time of Cholera.

You could write the novel’s central idea thus:

‘When Fermina Daza’s husband dies, a former suitor who’s loved her since courting her decades before shows up unexpectedly to pay his respects and declare his undying love.’

Given this dramatic, emotional chain of events, there are many possible plot points.

For example, the story could proceed to show:

- First major plot point: Fermina’s reaction to her former suitor’s reappearance and declaration of love

- Second: How her suitor Florentino acts after Fermina embraces or rejects him

- Third, fourth, fifth: Flashback scenes show the plot points explaining their current feelings towards each other

Each of these is ripe for surprise, conflict, and strong emotions. These are the ingredients that make stories compelling.

2. Find plot points showing desires, motivations and setbacks

Characters feel most believable when we understand the causes and effects driving them.

Brainstorming what your character wants and the emotions driving these desires is key to finding character-driven plot points.

For example, in a spy saga, your novel might open with a character running from a high-security facility. Perhaps they’re clutching valuable stolen documents.

In this instance, information is the desire that drove your character to act. Fear (of being caught) is the emotion propelling them towards the next situation (their escape or capture).

It would make sense to brainstorm plot points that complicate your spy’s situation further. They could:

- Drop a personal item mid-flight that security picks up and enables the antagonists to get on their trail

- Be caught, making what happens to them next an open question

- Discover once they reach safety key documents they need are missing

Clear character desires, motivations and setbacks help maintain a sense of purpose and direction in your story.

3. Place plot points at important structural junctures

One reason it’s helpful to think in plot points is that having a summary-like overview helps you structure and keep events developing. Place plot points at key structural points (for example, the end of your first chapter) to create hooks and cliffhangers. These structural devices keep readers intrigued and entertained.

Let’s return to the Marquez example. Marquez ends his first chapter, most of which focuses on Fermina’s husband and establishing the book’s setting, with Florentino revealing his undying love to Fermina.

On the second-last page of the chapter, we read these key lines of dialogue:

“Fermina,” he said, “I have waited for this opportunity for more than half a century, to repeat to you once again my vow of eternal fidelity and everlasting love.”

Placing this revelation so close to the end of the chapter (in such an inappropriate setting – the hearer’s husband’s funeral) naturally creates dramatic suspense.

The full first major plot point is completed by Fermina’s rejection of this advance:

‘Her first impulse was to curse him for profaning the house when the body of her husband was still warm in the grave. But the dignity of her fury held her back. “Get out of here,” she said. “And don’t show your face again for the years of life that are left to you.” She opened the street door, which she had begun to close, and concluded:

“And I hope there are very few of them.”‘

This furious reaction shows a clear setback for Florentino. Yet Marquez ends the chapter by introducing a further note of uncertainty. It’s possible Fermina is more conflicted than her first outburst lets on:

‘…she slept, sobbing, without changing position on her side of the bed, until long after the roosters crowed […]. Only then did she realize that she had slept a long time without dying, sobbing in her sleep, and that while she slept, sobbing, she had thought more about Florentino Ariza than about her dead husband.’

Marquez thus brings his first chapter to a close on a major revelation and further complication: ‘What will Fermina do next?’ we wonder.

4. Create points of no return

Your first plot point doesn’t have to be a point of no return for your character. After all, your first major event might be a key historical event in a prologue, for example, showing the general historical situation that shapes all your character’s lives (e.g. the events explaining how your characters ended up in the setting that opens your story).

Still, a plot point that shows an event there is no return from is a useful narrative device. Because it creates forward momentum.

Florentino revealing to Fermina that he’s still in love with her is an example of this type of plot point. He can’t ‘unsay’ what he’s told her. It’s a turning point for her too – she can’t un-hear it. Their meeting at the end of chapter 1 also has a decisive outcome.

She forbids Florentino’s further approach (a literal point of ‘no return’), yet we know because of his determined holding out for this moment he’s unlikely to give up so easily.

A strong point of no return:

- Shows a decisive situation that shapes your character’s future actions: Ask yourself what choices a point of no return leaves your characters

- Has an emotional component: How does a character feel about what happens at the point of no return? Will Florentino drown his sorrows in a bar and get in a fight? Sit dejectedly in his room writing lovelorn bad poetry? Or will he pursue Fermina with even more fervour?

- May bring a change in setting, viewpoint character or time period: From the love declaration on, Marquez begins alternating time periods, giving us a glimpse into Fermina and Florentino’s mutual past

5. Create and arrange summaries of each plot point

Consciously plan and structure how each plot point flows to the next. This will leave fewer irrelevant ‘filler’ scenes to cut when you revise.

You could create visual timelines with dates showing individual plot points and when they occur, as well as which characters they involve. For example:

If you prefer to focus on the words and not make visual aids, use a simple tool like the Scribble Pad on Now Novel. You can name individual scribbles (brief 800-word extracts) with a short description of what happens during this particular plot point. Then add more expansive detail in the text of your extract itself. You’ll build up a sequence of handy plot point summaries:

What’s more, you can share these individual plot points for constructive feedback from other writers to decide which plot points work best for your central story idea.

Focusing on key events in your story that actively drive your plot and your characters’ actions and decisions will help keep your story focused, lean and intriguing.

Related Posts:

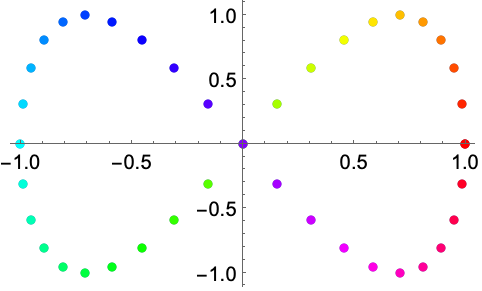

The Q-Q plot, or quantile-quantile plot, is a graphical tool to help us assess if a set of data plausibly came from some theoretical distribution such as a Normal or exponential. For example, if we run a statistical analysis that assumes our dependent variable is Normally distributed, we can use a Normal Q-Q plot to check that assumption. It’s just a visual check, not an air-tight proof, so it is somewhat subjective. But it allows us to see at-a-glance if our assumption is plausible, and if not, how the assumption is violated and what data points contribute to the violation.

A Q-Q plot is a scatterplot created by plotting two sets of quantiles against one another. If both sets of quantiles came from the same distribution, we should see the points forming a line that’s roughly straight. Here’s an example of a Normal Q-Q plot when both sets of quantiles truly come from Normal distributions.

Now what are “quantiles”? These are often referred to as “percentiles”. These are points in your data below which a certain proportion of your data fall. For example, imagine the classic bell-curve standard Normal distribution with a mean of 0. The 0.5 quantile, or 50th percentile, is 0. Half the data lie below 0. That’s the peak of the hump in the curve. The 0.95 quantile, or 95th percentile, is about 1.64. 95 percent of the data lie below 1.64. The following R code generates the quantiles for a standard Normal distribution from 0.01 to 0.99 by increments of 0.01:

We can also randomly generate data from a standard Normal distribution and then find the quantiles. Here we generate a sample of size 200 and find the quantiles for 0.01 to 0.99 using the quantile function:

So we see that quantiles are basically just your data sorted in ascending order, with various data points labelled as being the point below which a certain proportion of the data fall. However it’s worth noting there are many ways to calculate quantiles. In fact, the quantile function in R offers 9 different quantile algorithms! See help(quantile) for more information.

Q-Q plots take your sample data, sort it in ascending order, and then plot them versus quantiles calculated from a theoretical distribution. The number of quantiles is selected to match the size of your sample data. While Normal Q-Q Plots are the ones most often used in practice due to so many statistical methods assuming normality, Q-Q Plots can actually be created for any distribution.

In R, there are two functions to create Q-Q plots: qqnorm and qqplot.

qqnorm creates a Normal Q-Q plot. You give it a vector of data and R plots the data in sorted order versus quantiles from a standard Normal distribution. For example, consider the trees data set that comes with R. It provides measurements of the girth, height and volume of timber in 31 felled black cherry trees. One of the variables is Height. Can we assume our sample of Heights comes from a population that is Normally distributed?

That appears to be a fairly safe assumption. The points seem to fall about a straight line. Notice the x-axis plots the theoretical quantiles. Those are the quantiles from the standard Normal distribution with mean 0 and standard deviation 1.

The qqplot function allows you to create a Q-Q plot for any distribution. Unlike the qqnorm function, you have to provide two arguments: the first set of data and the second set of data. Let’s look at the randu data that come with R. It’s a data frame that contains 3 columns of random numbers on the interval (0,1). Random numbers should be uniformly distributed. Therefore we can check this assumption by creating a Q-Q plot of the sorted random numbers versus quantiles from a theoretical uniform (0,1) distribution. Here we create a Q-Q plot for the first column numbers, called x:

The ppoints function generates a given number of probabilities or proportions. I wanted the same number of values in randu$x, so I gave it the argument length(randu$x), which returns 400. The qunif function then returns 400 quantiles from a uniform distribution for the 400 proportions. I save that to y and then plot y versus randu$x in the qqplot function. Again, we see points falling along a straight line in the Q-Q plot, which provide strong evidence that these numbers truly did come from a uniform distribution.

What about when points don’t fall on a straight line? What can we infer about our data? To help us answer this, let’s generate data from one distribution and plot against the quantiles of another. First we plot a distribution that’s skewed right, a Chi-square distribution with 3 degrees of freedom, against a Normal distribution.

Notice the points form a curve instead of a straight line. Normal Q-Q plots that look like this usually mean your sample data are skewed.

Next we plot a distribution with “heavy tails” versus a Normal distribution:

Notice the points fall along a line in the middle of the graph, but curve off in the extremities. Normal Q-Q plots that exhibit this behavior usually mean your data have more extreme values than would be expected if they truly came from a Normal distribution.

For questions or clarifications regarding this article, contact the UVA Library StatLab: statlab@virginia.edu

Points Plot Python

View the entire collection of UVA Library StatLab articles.

Plots Points On A Map

Clay FordStatistical Research Consultant

University of Virginia Library